Just before my trip to India, a terrible news broke out about a young lady who was brutally gang-raped in a moving bus and consequently died of her injuries. The incident must have stoked the mounting rage of the citizens because a series of protest marches followed. As expected, more reports of abuses and crimes against women flowed out of the news as these unsettling stories finally found a place in the public consciousness fuelling the outcry for justice.

On my first night in Delhi, I checked out the local news on TV, which is pretty much my practice every time I am in a different place despite the language barrier. I heard updates on the rape case and the beheading of Indian soldiers by Pakistanis at the border. I don’t plan to set foot in the contested district where it happened but my tour will get me 50 km to to the border.

Without meaning to, I was slowly drawn in to the richness of their history and their vast heritage, their struggles as a nation, the complexity of their religions, the long-held traditions and the diversity of their peoples. I slowly acquainted myself with the prevailing culture and the hard reality of the place I’m visiting by observing, asking questions and mingling with a few locals. I tried to feel the peoples’ pulse and understand from their point of view. I was extra careful, remembering that I’m only a guest and that I was never asked to come to their place, but invited myself in. I played by the rules. I dressed very conservatively sometimes to the point of inconvenience.

A few days into the tour, I began noticing the designs of temples, palaces and cities with respect to the place of women in them or rather behind them, literally. In some cities, I was told that women back in the day were prohibited to be seen in public. Small intricate windows and screened balconies in City Palaces were built so royal women can see everyday life without appearing in public. While ordinary women got away when secret chambers within the cities were built so they can pass by and mingle with other women. The fact that special provisions had to be made to accommodate a little bit of women’s liberty, women were such a huge inconvenience back then.

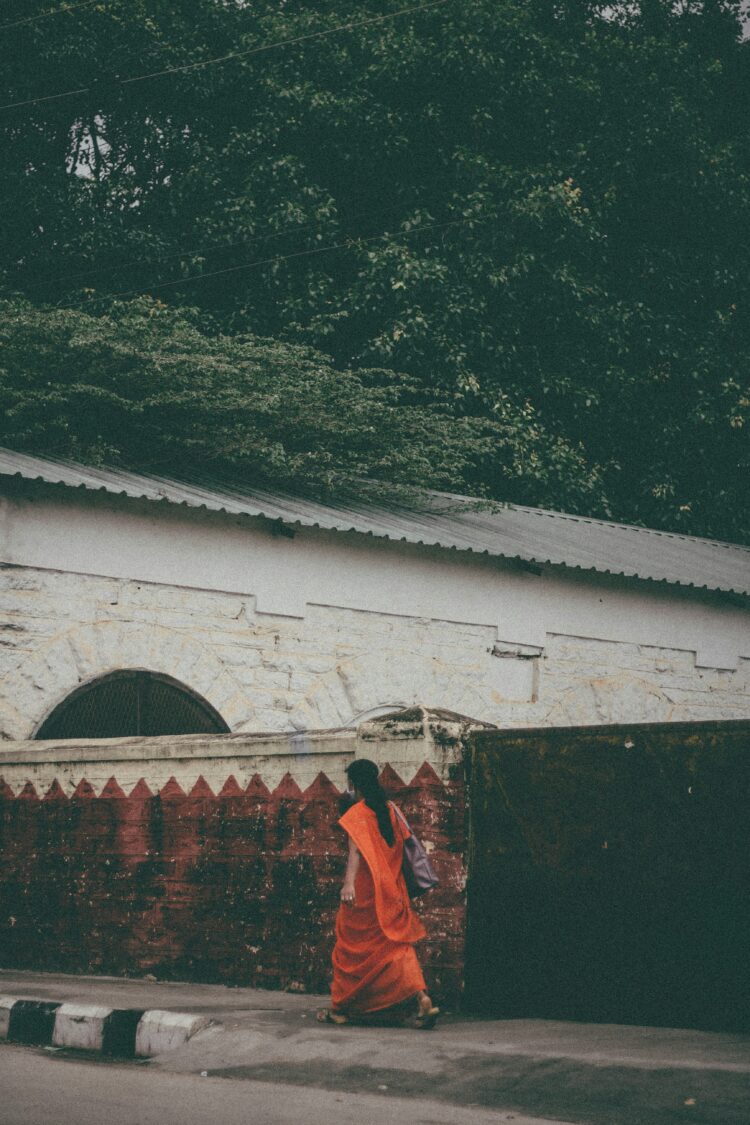

Going farther into more rural places that seemed untouched by time except for evidence of the ubiquitous cellphones, it was more apparent and felt. All working personnel from guards, storekeepers, hotel staff were men. I searched and searched for women but they were inside their houses. I felt embarrassed to be traveling solo as a woman openly, brazenly entering the city wearing my hair long, freely strolling in this place where local women dressed in traditional clothes were kept out of sight. Despite my thick turtleneck long-sleeves, long pants and shawl, I felt I still had to cover my hair. It seemed like I owe an apology for this over reaction but I felt men’s direct gaze too,

There was one crucial point when I needed a woman for some kind of emergency but there was just nobody to approach. I felt I was such an inconvenience. So I ended up asking fellow female travellers. It is also through encounters with fellow travellers (mostly older Caucasians) that I began to observe how the locals are relating with the “untouchables” and I took particular interest in the untouchable women in my photos. The British couple I was chatting with over breakfast described their observations: locals talk down to the untouchables. The discrimination is clear and present.

It was all very different especially coming from a family where men are outnumbered (just my father) with a mother and 4 daughters. Growing up, my sisters and I were encouraged to do well, be free and independent, take charge, lead. Gender was never an issue until it was. I had a voice until I realised that too, was constrained. In my line of work as a young lady with a careless spirit, I would speak directly to military to leave us alone and to a male tribe elder who would later yell back at me and the rest of people I’m representing for 3 hours or so, as if to put me in place.

So it is also in this light that I recall a visit in our office by a very high-ranking female American corporate. She hung out a little with my female colleagues and myself. She started speaking about how pleased she was to see a large group of women like us in the workforce, more so scientists and engineers and that this seemed rare based on what she’s seen around Asia. In my little bubble in my home country, I reasoned out and argued with people, regardless of their gender. Later on, I dealt a lot with men because of their prevalence in the kind of work that I do, but in ways where I did not shrink. But as I grew older and relocated to where I became the minority, gender and race became an ever growing and present reality.